I. Introduction

In metal fabrication, bending the metal sheet to various shapes and structures is indispensable. The machine used for this process is press brake and pan brake.

Each machine has its own advantages, so it is pivotal for manufacturers to know their differences to make a wise choice based on their specific requirements.

Press brake, also called brake press, is the most common type in metal industries, which can handle thicker metals and more complicated components effectively compared with other sheet metal brakes.

Press brakes have mechanical and hydraulic assemblies and can be widely used in multiple metal fabrication projects.

Meanwhile, a pan brake, also called a box and pan brake or finger brake, aims to generate a bend along the edge of the metal sheet.

It uses metal sheets to produce boxes, trays, and flat pans and is more suitable for achieving precise bending for specific applications.

Our passage aims to compare the two machines in characteristics and application spheres to help readers better understand their functions and advantages in the metal fabrication industry.

Via comparison, we can learn when to choose press brakes, when to choose pan brakes, and how they satisfy industrial needs.

II. Understanding Press Brakes

Definition and basic mechanics of press brakes

Press brake utilizes the punch and die to exert pressure on a piece of metal sheet, making it bend or form the required angle and shape.

Place the metal sheet between the punch and die, then the press brake punch will generate the necessary force to bend.

The press brake can be operated by hand, hydraulic, or other power sources and is precisely determined by the type of press brake.

Types of press brakes

Based on the driven ways, the press brake can be divided into the following types:

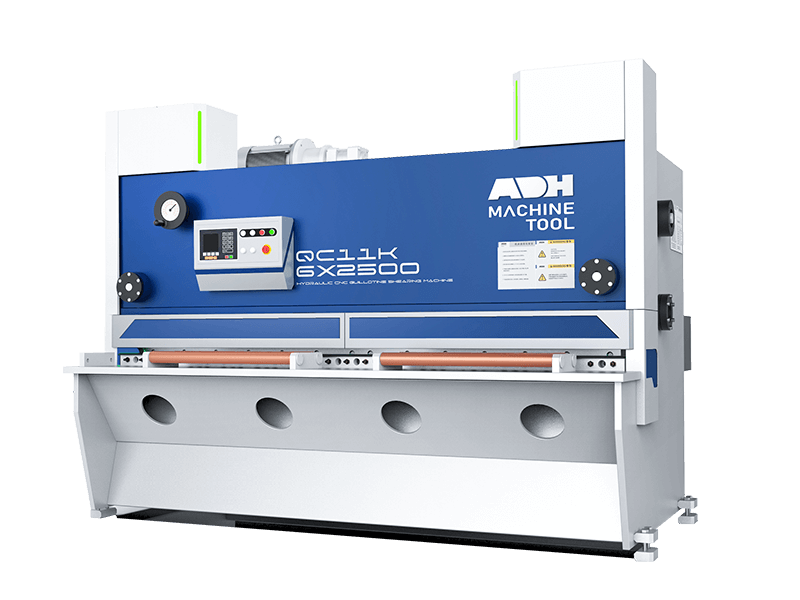

Hydraulic press brake: this type uses a hydraulic cylinder to control the ram movement, which features strong power, controllable speed, and good stability. Its vital parts are a hydraulic cylinder, ram, clamp, die, and punch.

Mechanical press brake: it uses a mechanical flywheel to generate force for bending metal sheets, which is famous for high speed and is suitable for mass production. Its main components include a flywheel, ram, clamp, die and punch.

Servo press brake: It is driven by a servo motor and can achieve more precise control and lower consumption. Its main parts are the motor, ram, clamp, die, and punch.

Common uses and key features

The main functions of the press brake include the adjustable back gauge used to precisely position, programmable controls used for automatic bending sequence, and safety functions for protecting the operators during the bending operation.

Its key characteristics include high-precision control, strong adaptability (handling various thicknesses and types of metal sheets), and high-level automation.

Advantages in metalworking

Press brake boosts many advantages ****in the following aspects:

High-precision: it uses an advanced control system to control the bending process accurately, thus acquiring precise and repeatable results.

Strong adaptability: it can deal with different types and thicknesses of metal materials.

High-efficiency: it can significantly improve production efficiency, especially for mass production.

Customizable: it can create custom bends and shapes via programming control and tooling choices to meet the design requirements.

III. Exploring Pan Brakes

Definition and primary functions

Pan brakes, also called box and pan brakes or finger brakes, are machine tools used for metal fabrication and sheet metal manufacturing.

This machine is mainly used for bending and processing thin metal sheets and generates the required angles and shapes, including boxes, trays, and other three-dimensional components.

Pan brakes are widely used in many industries, such as HVAC, metal fabrication, and general sheet metal fabrication.

The main parts of the pan brake are the clamp, segmented fingers, dies, and punch. Compared with the press brake, the pan brake is simpler and boosts the creation of tight angles and short edges.

However, the pan brake lacks the precision and control ability of a CNC or NC press brake.

Variations (like finger brakes)

A finger brake is a specific pan brake, including segmented fingers or bars, which can be adjusted to generate different types of bends and shapes on the metal sheet.

This variation can achieve more powerful versatility and precision when forming intricate and custom metal sheet accessories.

Unique features and typical applications

Pan brake features clamp parts for fixing the metal sheet, a straight edge for aligning, and a bending leaf for exerting pressure and generating bends.

These machines are usually used to produce boxes, flat pans, and trays of specific sizes and shapes.

Pan brakes are highly beneficial for creating components that need complex bends and folding, such as electrical enclosures, piping systems, and special metal enclosures, and are particularly suitable for customized small-scale production.

Benefits in specific projects

In specific programs, the advantages of pan brake are just as follows:

Customizable bending: pan brake is suitable for producing unique shapes or sizes of metal parts

Simple operation: compared with the press brake, the pan brake is more accessible to operate and set, especially suitable for occasions that do not require high precision.

Cost-effectiveness: the cost-effectiveness is high when the pan brake produces small-scale and custom projects. Through achieving custom metal parts inner manufacturing, the pan brake can help reduce specific programs outsourcing costs and delivery times.

Less occupation: compared with a large-scale press brake, the pan brake features a small volume, suitable for working areas with restricted space.

Versatility: the adjustable finger of finger brakes offers flexibility for generating various shapes and sizes, thus producing multiple metal products.

IV. Key Differences Between Press Brakes and Pan Brakes

Comparison of capabilities and limitations

Press brake: this machine can be used to bend more widespread materials and thicker specifications (up to 20 mm). It has higher precision and repeatability, suitable for complex and accurate bending tasks. However, it has a more robust power ability, which can not reduce radius like pan brakes and needs more operation skills.

Pan brake: pan brake can be applied to bend materials and specifications (up to 6 mm). It is more flexible, convenient for small- and medium-scale projects, and suitable for simple and custom-bending needs. Its working area is smaller than the press brakes. However, its precision and bending intricacy are worse than the press brake.

Materials and thicknesses

Press brake: it can handle thicker and heavier metal sheets, suitable for materials with various solidness and intensities.

Pan brake: it is more suitable for dealing with thin metal sheets, especially for small components requiring complex shapes.

Cost implications and space requirements

Press brake: its initial cost is relatively high, it can replace multiple pan brakes, and needs more maintenance and operation training. Also, it occupies a lot of space.

Pan brake: it has low cost and is suitable for small-scale workshops and a restricted budget. Also, it occupies fewer. However, it needs multiple machines for mixed production.

Situations where each is more advantageous

Press brake: it is suitable for mass scale, high precision industrial production, especially when dealing with large size or thicker materials.

Pan brake: it is suitable for small-scale or custom production, especially for restricted budget or space working environments.

V. Choosing the Right Brake for Your Project

Factors to consider

Project complexity and precision requirement: for projects that need high precision and intricate bending, the press brake is a wise choice.

Types of materials and thickness: the press brake is suitable for thicker and solid materials, while the pan brake is suitable for thinner metal plates below 6 mm.

Production volume: press brakes are suitable for mass production because they offer faster production speed and higher repeatability.

Space and budget restrictions: as for restricted space and budget, the pan brake will be an ideal choice for you.

| Factor | Pan Brake | Press Brake |

|---|---|---|

| Material Thickness | Thinner mild steel or aluminum under 6mm | Thicker gauges over 6mm |

| Change Frequency/Bend Radii | Frequent changes or tight radii | Straightforward bends without tight radii |

| Floor Space | Limited | Not a constraint (can replace multiple pan brakes) |

| Production Volume | Not specified | Higher volumes |

Pros and cons based on project requirements

Press brake:

Pros: high precision and repeatability, suitable for complex and mass scale production, and handle thicker materials.

Cons: high cost, occupies considerable space, more complicated operation and maintenance

Pan brake:

Pros: low cost, few occupations, simple to operate, and suitable for small-scale and custom production

Cons: not suitable for intricate and mass-scale production, restricted precision, and applicable material thickness.

VI. FAQs

1. What are the disadvantages of press brakes?

Press brake occupies much more space, and purchasing and installation costs are high. And it is not suitable for bending tight and complicated radius.

It is more suitable for simple bending. The setting process may be longer than that of other machines, which reduces the flexibility of small-scale or frequent working replacement.

2. Why is it called a box and pan brake?

Box and pan brake is a kind of metal sheet press brake, which is used to bend the metal sheet into boxes and pans.

The name originates from the fact that this machine can bend various metal sheets into boxes and pans with various sizes and shapes, including the boxes and pans with sides that are higher than the depth of the machine's jaws.

This machine is also called a finger brake because of its adjustable fingers, which can be repositioned to bend the metal sheet into complicated shapes.

3. What is the press brake basic technique?

Position: press brakes use a precise back gauge, and put the metal sheet between the upper die and bottom die to process the bending position.

Bending: start the press brake ram and exert a much downward force to press the metal sheet into the shaped cavity of the dies.

Forming: the upper and bottom die work together, and the metal sheet can be formed into the required shape and angle according to the die outline.

Repeating: the press brake can precisely achieve repeatable bending by adjusting the back gauge to produce multiple components in manufacturing.

4. What is a CNC press brake vs an NC press brake?

The difference between the NC press brake and the CNC press brake is that the latter owns a more advanced controller.

This allows intricate program operation, which improves the accuracy and automatic levels. The CNC press brake is more suitable for complicated workpieces and mass production.

VII. Conclusion

In our passage, we delve into the importance of the press brake and pan brake in the metal fabrication and manufacturing industry and compare their functions, advantages, and uses.

Whether the precise control of the press brake or specific advantages of the pan brake, choosing the proper equipment is vital to ensure the best working effect and improve efficiency.

When choosing the proper equipment, considering the project requirement, material characteristics, cost, and space restriction is paramount.

Each type of press brake has a unique feature; the key is to find the one that fits your specific requirements.

Now, you probably have an initial understanding of which press brake fits you most. But before making the final decision, knowing more about the details and seeking professional advice is necessary.

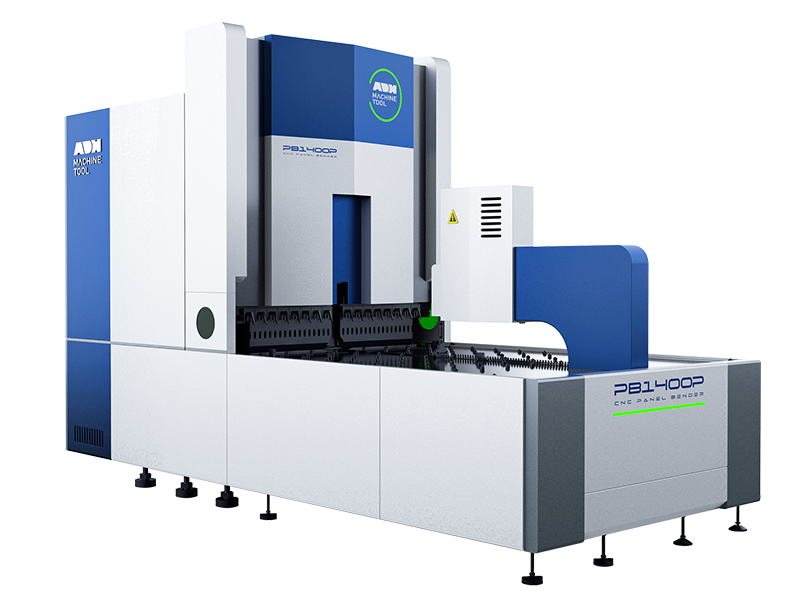

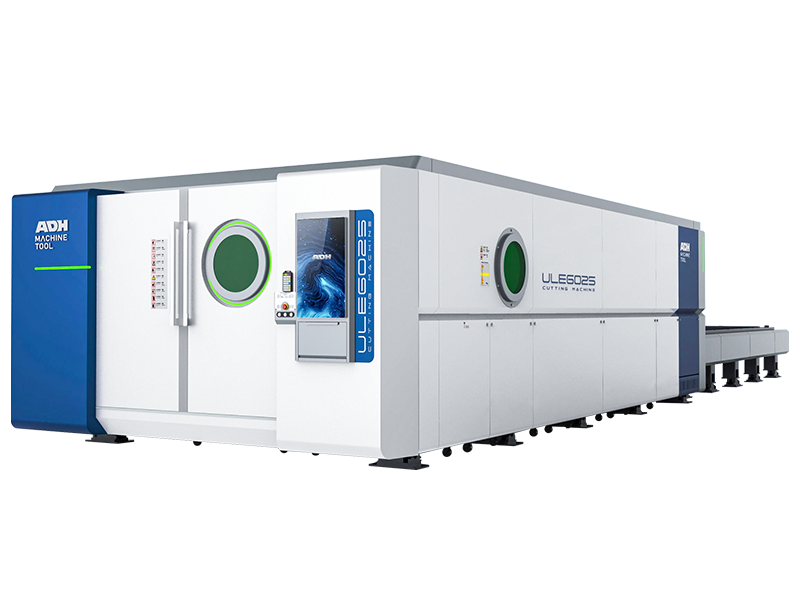

ADM Machine Tool is a platform where you can find your ideal machine and learn more about our products.

Also, you can consult our experts. They will offer you specific advice and quotes according to your custom needs.

We look forward to cooperating and helping you achieve the program goals.